When I was a teenager and my father realized the true extent of my passion for the movies, he gave me a slim paperback titled simply “Picture.” The author was Lillian Ross. I’d read Arthur Knight and Manny Farber and Bosley Crowther and Stanley Kaufman, and, of course, Pauline Kael. But Ross was new to me. After reading the book, which many consider the best book ever written about the making of a motion picture, I never again missed an opportunity to read anything by Lillian Ross. (Who, not incidentally, while born in Syracuse, was raised in Brooklyn.)

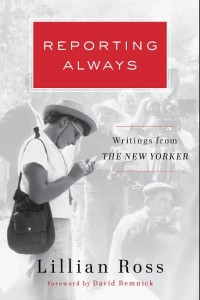

Now, with the publication of “Reporting Always: Writings from The New Yorker,” with a forward by The New Yorker’s editor, David Remnick, we have the opportunity to reacquaint ourselves with the work of Ms. Ross — and to make new discoveries. For me, without doubt, the best of these discoveries is her droll and deadpan profile of the larger-than-life Brooklynite Sidney Franklin, titled “El Unico Matador.” (Not incidentally, this was Ross’s first New Yorker profile that appeared under her own byline.)

At first glance, Franklin, born Stanley Frumpkin in 1903 into an Orthodox Jewish family that had fled Imperial Russia for America in 1888, seems too outlandish to be true. The son of an NYPD cop (who was assigned to Brooklyn’s 78th Precinct), a closeted gay man (interestingly, the Eagle, which closely chronicled Franklin’s rise, was, in the 1840s, edited by another closeted male, Walt Whitman), a student of the legendary matador Rodolfo Gaona and friends with, among others, writer Barnaby Conrad, film director Budd Boetticher and James Dean (a great aficionado of bullfighting), Franklin went on to have an improbable, extraordinary life. The deeper one gets into Ross’s article, the more one realizes what a fantastic story she is telling. (In fact, in his biography of Hemingway, with whom Franklin had a fraught friendship, A.E. Hotchner writes that “Lillian Ross’s career with The New Yorker was founded on the success of her profile of the bullfighter Sidney Franklin.”)

As Ross recounts, Franklin became a matador after running away from home to Mexico. He fought bulls in Spain, Portugal, Colombia, Panama and Mexico. In “Death in the Afternoon,” Hemingway wrote of Franklin that “[He is] brave with a cold, serene and intelligent valor but instead of being awkward and ignorant he is one of the most skillful, graceful and slow manipulators of a cape fighting today.”

The reader quickly realizes that Ross is captivated by Franklin; where other reporters might have been barbed and mocking, Ross gives Franklin the benefit of the doubt. Even Franklin’s own sympathetic biographer, Bart Paul, notes that “El Torero de la Torah” (as his legion of Spanish fans dubbed him) was prone to exaggeration and tall tales. Wisely, Ross lets Franklin do most of the talking: “It’s all a matter of first things first. I was destined to taste the first, and the best, on the list of walks of life … I was destined to shine. It was a matter of noblesse oblige.”

Noblesse oblige is a term that Franklin uses a lot. Once, while watching a bullfight in Mexico, he was seated next to a British psychiatrist. They had a conversation, captured by Ross, straight out of Lewis Carroll, by way of Groucho Marx:

“While a dead bull was being dragged out of the ring, Franklin turned to the psychiatrist. ‘Say, Doc, did you ever get into the immortality of the crab?’ he asked. The psychiatrist admitted that he had not, and Franklin said that nobody knew the answer to that one. He then asked the psychiatrist what kind of doctor he was. Mental and physiological, the psychiatrist said. ‘I say the brain directs everything in the body,’ Franklin said. It’s all a matter of what’s in your mind.’ ‘You’re something of a psychosomaticist,’ said the psychiatrist. ‘Nah, all I say is if you control your brain, your brain controls the whole works.’ The psychiatrist asked if the theory applied to bullfighting. ‘You’ve got something there, Doc,’ said Franklin. `Bullfighting is basic. It’s a matter of life and death. People come to see you take long chances. It’s life’s biggest gambling game. Tragedy and comedy are so close together they’re part of each other. It’s all a matter of noblesse oblige.’”

Who but Ross could have captured that? And then, with impeccable reportorial instincts, gotten out of the way? One also realizes that, in many ways, she set the template for a certain New Yorker style. (The Franklin profile was written in 1949.) The hallmarks of this style are bemusement, curiosity, meticulous attention to detail and, especially refreshing in our age of internet-fueled snark, generosity. It would have been so easy to mock Franklin; Ross never took that bait.

By email, I ask Remnick about the Franklin piece in particular and Ross’s reportorial prowess in general.

“The Sidney Franklin profile is one of my favorites. You don’t find many Brooklyn bullfighters these days. There must be something in the kale or the air or something. It doesn’t matter. What was so wonderful about Lillian’s piece, and all of her pieces, was her eye for a story and her ear for the way people tell them. She remains a master.”

Even when she is profiling (in “How Do You Like It Now, Gentlemen?,” written in 1950) someone with as huge a target on his back as Ernest Hemingway, Ross never takes a cheap shot. From Remnick’s Introduction: “To her astonishment and Hemingway’s, some readers thought the piece was a hatchet job, a work of aggression that besmirched the reputation of a great literary artist. Which seemed ridiculous to both writer and subject. Hemingway and Ross had become close, and he went to great lengths to reassure her of their enduring friendship: ‘All are very astonished because I don’t hold anything against you who made an effort to destroy me and nearly did, they say,’ he told her. ‘I can always tell them, how can I be destroyed by a woman when she is a friend of mine and we have never even been to bed and no money has changed hands?’ His advice to her was clear: ‘Just call them the way you see them and the hell with it.’”

Ross took Hemingway’s advice, and for the past 65 years and counting, she’s never approached her craft any other way. How fortunate we are to have this new collection (which also includes profiles of Fellini, Al Pacino, Robin Williams, Maggie Smith and Judi Dench) — and to have this diminutive dynamo (it’s hard to get that Franklin patois out of my head) still out there with pad and pencil. Somehow, I’m sure she doesn’t use a Tablet.