When the curtain rises on the new production of Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible” at the Walter Kerr Theater (which boasts the dream cast of Saoirse Ronan, the star of “Brooklyn;” Ben Whishaw; Sophie Okonedo; and Ciarán Hinds), the audience sees a gloomy classroom with a blackboard, dim, drab overhead lights and three rows of seated teenage schoolgirls, in prim, black and gray uniforms with knee socks, sleeveless pullovers and blazers, all facing forward with their backs to the audience.

Faintly, the spectators hear a chorus of girls’ voices, but the words are unintelligible. The setting and the sounds are both ordinary and spooky. Before there is a chance to decide which description fits best, the curtain descends, and then quickly rises again on the same set, but now fully lit, with a young girl prone on a gurney, being administered to by a clergyman. In the background stands another schoolgirl, brooding and concerned.

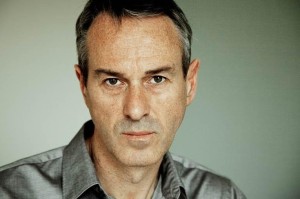

Theatergoers who saw last year’s “Antigone” with Juliette Binoche at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) and the recent revival of Miller’s “A View from the Bridge” will recognize where they are: in Ivo-land. The Belgian-born Ivo van Hove is everywhere; last November he also directed the limited run of “Lazarus,” a musical collaboration between the late David Bowie and the Irish playwright Edna Walsh. With “The Crucible,” which officially opens this Thursday night, van Hove makes his Broadway debut.

He is, indisputably, having his New York moment.

Recently, the Eagle spoke with van Hove by telephone about his propensity for tackling the theatrical canon, his unique approach to rehearsal and, in particular, the current production of “The Crucible.”

Eagle: Nothing in the theatrical or cinematic canon — Euripedes, Shakespeare, O’Neil, Miller, stage adaptations of Bergman, Cassavettes, Pasolini, Viscounti films — seems to intimidate you. How did you become so fearless?

Van Hove: Well, you know, you only live your life once. Why not take chances? Before we begin a production, I always tell my creative team that we’re in the Olympics. Our goal should be the gold medal. The stage work and the film adaptations I choose to do are always driven by the actors, not by the beauty of the visuals or the physical design. As a novelist does through his writing, I want to express through my theatre work, my feelings, my passions.

Eagle: You have said about “The Crucible” that “…it is not a play about good and evil; it is about evil within goodness and goodness within evil.” Can you elaborate?

Van Hove: Now that I have done two Miller plays, what I have discovered is that he deals with ethical problems, often in black and white terms. But I don’t see things as that black and white. Take Abigail [Williams, who is the catalyst for the Salem witch hysteria and subsequent trials]. Listen carefully to what she says in the first act, when she reproaches John Proctor for ending their relationship. She really felt, for the first time in her life, respected as a woman. She’s 17. The fact that John, her first lover, rejects her is earth-shattering. She is very fragile.

For the Puritans, being a young girl meant three things: You had to always obey your parents (especially regarding even the hint of anything sexual); you had to became a servant, as Abigail was for John and Mary Procter; and you were not allowed to truly transition from a girl to a woman. Abigail is so often played as the evil villainess of “The Crucible.” But I don’t see her that way. Remember, she is the only character to escape Salem, to seek her freedom. John and Mary stay — and pay the price.

Eagle: Why do you insist that your actors be “off-book” from the first day of rehearsal? And why, in rehearsal, do you have your actors work steadily through the text, reaching the end of the play just before the first public performance?

Van Hove: I believe it is great for actors, in rehearsal, to discover the play. After all, that’s the way one lives one’s life —not knowing from one day to the next what is going to happen. As with life, there should be uncertainty; I want my actors to unravel the play, scene-by-scene, to react to the uncertainty as they would in real life. When I have the actors rehearse the play, day-by-day, in chronological order, I don’t have to give them a lot of instructions. They are coming to their own recognition of the text. Which also makes them more comfortable and more natural.

Eagle: Finally, since you have been so bold in taking iconic films (to cite just a few, Ingmar Bergman’s “Scenes from a Marriage,” John Cassavetes’s “Husbands,” Luchino Viscounti’s “Rocco and His Brothers”) and transforming them into theater, when are you going to adapt “Star Wars” for the stage?

Van Hove [at first not realizing the tongue-in-cheek nature of my question]: Oh, no, I don’t think…

Eagle: Sorry, I was joking.

Van Hove (laughing): I may be, as you said, fearless, but I’m not reckless!

The Crucible runs through July 17 at the Walter Kerr Theater.